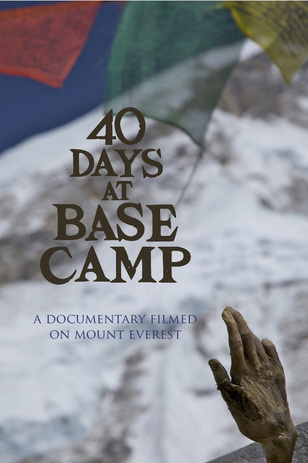

Director Dianne Whelan's, 40 Days at Base Camp is a compelling story about the journey to the top of the Mount Everest from base camp to summit, and those who choose to take on this incredible task.

Mount Everest has long been looked upon as “the climber's mountain” and reaching the summit, the highlight in a climber's career.

Climbers can range from the complete novice to the seasoned professional. The obstacles they face are not only physically and mentally challenging, but potentially life threatening. The mountain doesn't discriminate, claiming new lives every year: even trusted sherpas aren't immune to the temperament of the mountain.

tV: Where did the idea for this story come from?

DW: I always loved the story of Hillary and Tenzing, who were the first two to climb Everest in 1953. One was from the west and one was from the east and neither of them ever said who stood on the top first. I thought there was something very noble and beautiful and hopeful about that.

I was on assignment for Outpost magazine and they'd asked me to hike in to Everest base camp and write an article about the journey and the place. Being an avid climber myself, I welcomed the idea.

When I got there I was just blown away. First of all you have to hike for twelve days to get there on a centuries old trail through this very spiritual, religious environment. Then you get to base camp where there are eight hundred people from around the world living in these plastic tents on this glacier of rock and ice and nothing's alive. Then there's all the garbage. There's garbage there from the last couple of decades.

I'd heard stories of people's oxygen being stolen and climbers leaving other climbers to die on the mountain. There was a lot there that I could possibly cover in a story so I thought I'd go back and explore the place into a little more depth.

Generally speaking, 40 days is the length of one climbing season, so I thought I'd go back and spend 40 days and take a look at what was going on.

The mountain has always been a metaphor in literature, and generally for human ambition: reaching the top of the mountain, getting to the moon, getting in a boat and trying to discover undiscovered land. I thought of it as a new interpretation of that metaphor: a microcosm of the macrocosm because there are people from around the world. The desire to get to the top of that mountain is universal.

tV: You had such an array of people to choose from. How did you decide who to focus on?

DW: My background is in journalism so I'm used to getting to the scene and assessing the situation. Base camp takes about an hour and a half to hike from one end to the other so I needed to be within 15 to 20 minute's walk to my characters for logistical purposes.

I'd been there before so I knew who the key players were: for instance Apa Sherpa, who holds the world title for the most summits of Everest. I knew I wanted him but he didn't end up being as central a character as I wanted him to be because, though he's an amazing human being, he didn't convey well on camera so I needed other people to be able to convey that for me.

I also had some ideas too. There are basically three different types of climbers you find there; either they're corporately sponsored, or it's a government endeavour, or it's a personal endeavour.

I wanted to find representations of those different types of people.

I also didn't want to make a film just about professional climbers because that's not what the mountain's become. Even though it's the world's highest mountain it's been commercialized. People show up now with absolutely no climbing experience whatsoever, and never having seen snow, but they've got 90,000.00 to pay a company and try to get to the top.

There have been films made about the summit of the peak, but I was more interested in what's happening at the middle of the mountain.

tV: You must have had some pretty big challenges making this film.

DW: There's the logistics of getting six or seven hundred pounds of gear to eighteen thousand feet. You can get to within a hundred miles of the mountain then you're on a centuries old trail where everything has to be either carried on a horse's back or on the back of a yak.

I was the first woman to apply for a permit to film on the mountain and because of that they had a government person following me most of the trip. I had to spend most of my time evading this human being in order to get work done (laughs).

I'm used to rigourous physical experiences but this challenged me on more of a physiological level. The challenges were physical of course, but more about what was happening to my heart, my kidneys, and my brain. There's only 50% as much oxygen at base camp as there is at sea level. My resting heart beat was less than 120 beats a minute.

As a filmmaker making a film on Everest I have the same ethical conundrum as a person climbing the mountain: where are you going to draw your line; at what point is what you're doing dangerous to you; where do you push yourself.

Because it was 40 days at base camp it was a prolonged exposure to high altitude and there's no one really watching out for you, but you. I did suffer from some altitude sickness but fortunately nothing too severe.

There are 250 bodies on Everest of people who have died and when you die, generally your body is left there because it's really dangerous to take a body down. Even if they get it down, unless you're going to pay for a very expensive helicopter ride for that body to get to Katmandu and into refrigeration, it's going to decay before anyone can carry it down. You're either burned straight away once they get you to a lower altitude, or you're just left there.

While I was there this year a number of them started popping up a base camp. There's no one in control at base camp so these bodies weren't being removed or anything. It took about thirty days before anyone started doing anything, largely because I started pointing a camera at them.

It's bad etiquette in mountain climbing to take a photograph of a dead body. When you're climbing up the mountain, event though you're literally stepping over dead bodies, people generally don't photograph them: the sherpas don't like it, the climbing companies don't like it.

I only filmed one and I did it very respectfully from a distance and it was something I gave a lot of thought to. I was making a documentary and unfortunately this was a huge part of the story. That got me into a bit of trouble.

But that's what extreme filmmaking is: how you respond to the challenges (laughs).

tV: Are every one of the bodies documented? Do they know who they are?

DW: In some cases they did, especially the sherpas. If one of the bodies was a sherpa they'd know who he was. In that case they'd be able to take the body parts out and take them back to the village. There was another body, not the one that I found, of an American or British man who died about thirty years ago. It wasn't revealed to me at the time who he was. He had a watch on and it was traced back to his sister.

When I first discovered the body I filmed, I literally stumbled upon it. I made sure that when we filmed we stood way back and showed a lot of respect: not just to the Nepalese and sherpa customs but also to the dead person's family. They are uncannily well preserved for being in ice for thirty years.

The reason they were popping up at base camp was they probably died higher up on the mountain or even in the ice fall, one of the most dangerous parts of the climb, and due to climate change the glacier is melting rapidly. These bodies have basically been dragged down for decades in this moving ice as it's coming down the mountain. They might not ever have been found if not for the fact that the glacier is shrinking. The difference between 2007 and 2010 is shocking.

tV: You gave us a lot to think about in your film.

DW: It is the climate change issue and the environment, though I didn't make the film just for that thematic, because I think that's of the most importance to the Nepalese people. They, just like the Inuit, are suffering the most from Climate Change. A million people get their drinking water from Himalayan ice and what's going to happen when all that's gone?

Also, on a bigger picture this idea of mountain as metaphor. If this is the microcosm of the macrocosm, what does it say about us? I don't think there's a difference between whether it's an oil rig leaking in the gulf or a nuclear power plant that's leaking in Japan right now, they're all examples of human ambition that are out of balance.

There's nothing wrong with ambition. I didn't want to say these people were wrong for wanting to climb the mountain: people can make up their own minds about that. When human ambition gets out of balance that's when you get the garbage and that's where you get the destruction and that's when things start to go crazy. I was also just interested in making a film that was true to the documentary form: I wanted to make a piece of art.

check out VIFF for tickets and times

Climbers can range from the complete novice to the seasoned professional. The obstacles they face are not only physically and mentally challenging, but potentially life threatening. The mountain doesn't discriminate, claiming new lives every year: even trusted sherpas aren't immune to the temperament of the mountain.

tV: Where did the idea for this story come from?

DW: I always loved the story of Hillary and Tenzing, who were the first two to climb Everest in 1953. One was from the west and one was from the east and neither of them ever said who stood on the top first. I thought there was something very noble and beautiful and hopeful about that.

I was on assignment for Outpost magazine and they'd asked me to hike in to Everest base camp and write an article about the journey and the place. Being an avid climber myself, I welcomed the idea.

When I got there I was just blown away. First of all you have to hike for twelve days to get there on a centuries old trail through this very spiritual, religious environment. Then you get to base camp where there are eight hundred people from around the world living in these plastic tents on this glacier of rock and ice and nothing's alive. Then there's all the garbage. There's garbage there from the last couple of decades.

I'd heard stories of people's oxygen being stolen and climbers leaving other climbers to die on the mountain. There was a lot there that I could possibly cover in a story so I thought I'd go back and explore the place into a little more depth.

Generally speaking, 40 days is the length of one climbing season, so I thought I'd go back and spend 40 days and take a look at what was going on.

The mountain has always been a metaphor in literature, and generally for human ambition: reaching the top of the mountain, getting to the moon, getting in a boat and trying to discover undiscovered land. I thought of it as a new interpretation of that metaphor: a microcosm of the macrocosm because there are people from around the world. The desire to get to the top of that mountain is universal.

tV: You had such an array of people to choose from. How did you decide who to focus on?

DW: My background is in journalism so I'm used to getting to the scene and assessing the situation. Base camp takes about an hour and a half to hike from one end to the other so I needed to be within 15 to 20 minute's walk to my characters for logistical purposes.

I'd been there before so I knew who the key players were: for instance Apa Sherpa, who holds the world title for the most summits of Everest. I knew I wanted him but he didn't end up being as central a character as I wanted him to be because, though he's an amazing human being, he didn't convey well on camera so I needed other people to be able to convey that for me.

I also had some ideas too. There are basically three different types of climbers you find there; either they're corporately sponsored, or it's a government endeavour, or it's a personal endeavour.

I wanted to find representations of those different types of people.

I also didn't want to make a film just about professional climbers because that's not what the mountain's become. Even though it's the world's highest mountain it's been commercialized. People show up now with absolutely no climbing experience whatsoever, and never having seen snow, but they've got 90,000.00 to pay a company and try to get to the top.

There have been films made about the summit of the peak, but I was more interested in what's happening at the middle of the mountain.

tV: You must have had some pretty big challenges making this film.

DW: There's the logistics of getting six or seven hundred pounds of gear to eighteen thousand feet. You can get to within a hundred miles of the mountain then you're on a centuries old trail where everything has to be either carried on a horse's back or on the back of a yak.

I was the first woman to apply for a permit to film on the mountain and because of that they had a government person following me most of the trip. I had to spend most of my time evading this human being in order to get work done (laughs).

I'm used to rigourous physical experiences but this challenged me on more of a physiological level. The challenges were physical of course, but more about what was happening to my heart, my kidneys, and my brain. There's only 50% as much oxygen at base camp as there is at sea level. My resting heart beat was less than 120 beats a minute.

As a filmmaker making a film on Everest I have the same ethical conundrum as a person climbing the mountain: where are you going to draw your line; at what point is what you're doing dangerous to you; where do you push yourself.

Because it was 40 days at base camp it was a prolonged exposure to high altitude and there's no one really watching out for you, but you. I did suffer from some altitude sickness but fortunately nothing too severe.

There are 250 bodies on Everest of people who have died and when you die, generally your body is left there because it's really dangerous to take a body down. Even if they get it down, unless you're going to pay for a very expensive helicopter ride for that body to get to Katmandu and into refrigeration, it's going to decay before anyone can carry it down. You're either burned straight away once they get you to a lower altitude, or you're just left there.

While I was there this year a number of them started popping up a base camp. There's no one in control at base camp so these bodies weren't being removed or anything. It took about thirty days before anyone started doing anything, largely because I started pointing a camera at them.

It's bad etiquette in mountain climbing to take a photograph of a dead body. When you're climbing up the mountain, event though you're literally stepping over dead bodies, people generally don't photograph them: the sherpas don't like it, the climbing companies don't like it.

I only filmed one and I did it very respectfully from a distance and it was something I gave a lot of thought to. I was making a documentary and unfortunately this was a huge part of the story. That got me into a bit of trouble.

But that's what extreme filmmaking is: how you respond to the challenges (laughs).

tV: Are every one of the bodies documented? Do they know who they are?

DW: In some cases they did, especially the sherpas. If one of the bodies was a sherpa they'd know who he was. In that case they'd be able to take the body parts out and take them back to the village. There was another body, not the one that I found, of an American or British man who died about thirty years ago. It wasn't revealed to me at the time who he was. He had a watch on and it was traced back to his sister.

When I first discovered the body I filmed, I literally stumbled upon it. I made sure that when we filmed we stood way back and showed a lot of respect: not just to the Nepalese and sherpa customs but also to the dead person's family. They are uncannily well preserved for being in ice for thirty years.

The reason they were popping up at base camp was they probably died higher up on the mountain or even in the ice fall, one of the most dangerous parts of the climb, and due to climate change the glacier is melting rapidly. These bodies have basically been dragged down for decades in this moving ice as it's coming down the mountain. They might not ever have been found if not for the fact that the glacier is shrinking. The difference between 2007 and 2010 is shocking.

tV: You gave us a lot to think about in your film.

DW: It is the climate change issue and the environment, though I didn't make the film just for that thematic, because I think that's of the most importance to the Nepalese people. They, just like the Inuit, are suffering the most from Climate Change. A million people get their drinking water from Himalayan ice and what's going to happen when all that's gone?

Also, on a bigger picture this idea of mountain as metaphor. If this is the microcosm of the macrocosm, what does it say about us? I don't think there's a difference between whether it's an oil rig leaking in the gulf or a nuclear power plant that's leaking in Japan right now, they're all examples of human ambition that are out of balance.

There's nothing wrong with ambition. I didn't want to say these people were wrong for wanting to climb the mountain: people can make up their own minds about that. When human ambition gets out of balance that's when you get the garbage and that's where you get the destruction and that's when things start to go crazy. I was also just interested in making a film that was true to the documentary form: I wanted to make a piece of art.

check out VIFF for tickets and times

RSS Feed

RSS Feed