“Experience a comic book come to life.”

The Only Animal Artistic Director Kendra Fanconi has put together a fascinating, multi-media theatrical show that blends live stage action with 3D projection mapping and panelled action sequences that draw you into the centre of a comic book.

The story of Superman comes to life before you as we follow Joe, Jerry, and Joanne, on a journey of creation, love, and Superheroes.

Today we had the great pleasure of speaking with Fanconi about her latest creation.

tV: Where did the idea for this show come from?

KF: I had an acting teacher years ago who always told me to “move like a cartoon.” Like the Roadrunner cartoons and that kind of energy. I remember that I thought that would be fascinating to see. So there was that kind of physical interest.

Our team is largely composed of designers and we spent a long time building the world of the play together. We did some experiments off the side in some teaching that we did that was about live drawing, projecting live drawing, and new computer interfaces for live drawing. We thought it was really interesting so I started to look for a Canadian artist and eventually found my way to Joe Shuster and the golden age of comics, and Superman.

His life story is beautifully tragic so I thought, well here's a great biographical underpinning for a story. What the team eventually developed was that we'd tell the story as a living comic book. That allowed us to integrate all our interest in projection and live drawing into story-telling, into translating cartoon bodies to the stage, and all of these things.

tV: Your story is a blend of fact and fiction?

KF: The story in short form is that these two poor immigrant kids, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegal, came up with the idea for Superman in the early 30s. Joe was Canadian but his family had immigrated from Europe and had been in transit as displaced Jews. So these two Jewish kids came together and had this idea for Superman and then unknowingly signed away the rights for $130.

For ten years they worked for a page rate for Superman. When they started to ask for more money they were shown the contract and ejected from DC Comics.

They fought a lot of court battles and eventually made a tiny bit of traction but Siegal's daughter is still in the courts fighting for the rights today.

Shuster and Siegal eventually lost everything: their names were taken off Superman, and were really impoverished. At the same time, Joe was going blind so he lost his ability to draw at all.

The story is of these two friends and the original model for Lois Lane, who they both fell in love with when she was 16 and they were 18, 19 years old. There was kind of a 40-year love triangle between them.

Jerry Siegal was the loquacious one so so everything you have from interviews is from Jerry. There's one published interview with Joe Shuster given very late in his life to the Toronto Star. We have a lot of biographical events: we know the court cases, but there's very little that Joe said because he mainly drew.

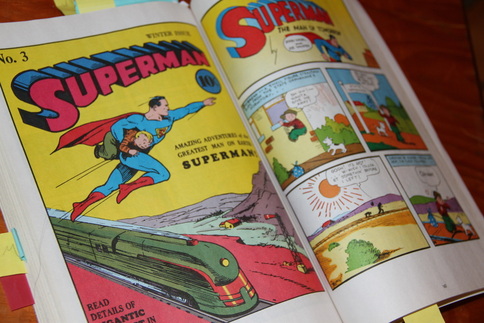

One of the things we did when we started the research was we got the eight volumes of the original comics and we looked at Superman as Shuster's alter ego.

The story of Superman comes to life before you as we follow Joe, Jerry, and Joanne, on a journey of creation, love, and Superheroes.

Today we had the great pleasure of speaking with Fanconi about her latest creation.

tV: Where did the idea for this show come from?

KF: I had an acting teacher years ago who always told me to “move like a cartoon.” Like the Roadrunner cartoons and that kind of energy. I remember that I thought that would be fascinating to see. So there was that kind of physical interest.

Our team is largely composed of designers and we spent a long time building the world of the play together. We did some experiments off the side in some teaching that we did that was about live drawing, projecting live drawing, and new computer interfaces for live drawing. We thought it was really interesting so I started to look for a Canadian artist and eventually found my way to Joe Shuster and the golden age of comics, and Superman.

His life story is beautifully tragic so I thought, well here's a great biographical underpinning for a story. What the team eventually developed was that we'd tell the story as a living comic book. That allowed us to integrate all our interest in projection and live drawing into story-telling, into translating cartoon bodies to the stage, and all of these things.

tV: Your story is a blend of fact and fiction?

KF: The story in short form is that these two poor immigrant kids, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegal, came up with the idea for Superman in the early 30s. Joe was Canadian but his family had immigrated from Europe and had been in transit as displaced Jews. So these two Jewish kids came together and had this idea for Superman and then unknowingly signed away the rights for $130.

For ten years they worked for a page rate for Superman. When they started to ask for more money they were shown the contract and ejected from DC Comics.

They fought a lot of court battles and eventually made a tiny bit of traction but Siegal's daughter is still in the courts fighting for the rights today.

Shuster and Siegal eventually lost everything: their names were taken off Superman, and were really impoverished. At the same time, Joe was going blind so he lost his ability to draw at all.

The story is of these two friends and the original model for Lois Lane, who they both fell in love with when she was 16 and they were 18, 19 years old. There was kind of a 40-year love triangle between them.

Jerry Siegal was the loquacious one so so everything you have from interviews is from Jerry. There's one published interview with Joe Shuster given very late in his life to the Toronto Star. We have a lot of biographical events: we know the court cases, but there's very little that Joe said because he mainly drew.

One of the things we did when we started the research was we got the eight volumes of the original comics and we looked at Superman as Shuster's alter ego.

We tried to lift what biographical information we could, and what we could about his character from the comics. That was hard as a writer because you don't want to guess wrong and you don't want to represent him improperly, so I did lots and lots and lots of research. For a while I thought I was writing a book about him instead of a play. Eventually I just began to hear his voice, and Jerry and Joanne, and took the plunge into fiction and wrote it. It is a fictionalized biographical account of his life I would say.

tV: What is the most surprising thing that you discovered along the way?

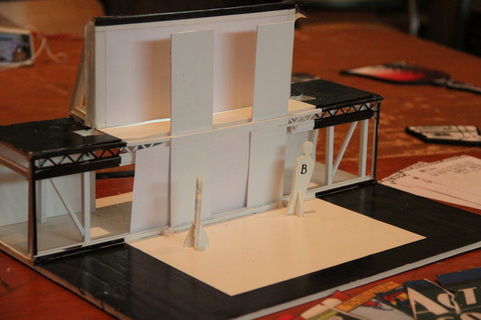

KF: I have a wonderful collaborator on the project. The other lead artist is a video artist named Keith Murray, who is designing all the projections. I think seeing the physical world of the play take shape was our starting point, where the stage was the blank page where we would develop the story as one would develop a comic.

tV: What is the most surprising thing that you discovered along the way?

KF: I have a wonderful collaborator on the project. The other lead artist is a video artist named Keith Murray, who is designing all the projections. I think seeing the physical world of the play take shape was our starting point, where the stage was the blank page where we would develop the story as one would develop a comic.

First you have the idea, and then you do a pencil sketch, and eventually you ink in your pencil sketching, erase out the pencil, and add colour. Then you create the panels and the word bubbles and things like that.

Then we realized that Joe's story was about loss so we thought that we would also chip away at those elements and strip things back down to the blank page.

I was really kind of surprised and delighted to see the visual motifs of the show. Everything on the stage is a projection so if you see white chairs or a big white drawing board, there are drawn chairs projected on these blank surfaces: there's a drawn door, and a drawn window, and a drawn sofa and such.

When we start adding colour after we've been in this stark black and white world for such a long time, there really is emotional life. That was a great surprise.

tV: How has it been working with the 3D element?

KF: We were really interested in both a theatrical representation of a 2D world, which we usually don't have in theatre either, and then bringing it in to 3D. We are in a traditional proscenium theatre that puts the audience at a distance looking in to the world, and we have these sliding panels that allow us to create comic books on stage where there's action and projected text. Here (indicates stage left on set model) there is a fire pole where the actors can quickly zip down and be in it again, so there's that kind of motion and fluidity within this panelled world.

Our projection comes from both the rear and the front. When it comes from the front, the actors have to be quite careful not to create shadows on the set, but when it comes from the rear you can really go right up to it and it's quite a visceral world.

We've experimented with all kinds of tropes within that 2D and 3D and use 2D props that bring us to that in-between world. The 2D wine glass that is secretly flipped to show a lower level of liquid.

It's a playful world because it is the comic books: it's entertaining.

Then we realized that Joe's story was about loss so we thought that we would also chip away at those elements and strip things back down to the blank page.

I was really kind of surprised and delighted to see the visual motifs of the show. Everything on the stage is a projection so if you see white chairs or a big white drawing board, there are drawn chairs projected on these blank surfaces: there's a drawn door, and a drawn window, and a drawn sofa and such.

When we start adding colour after we've been in this stark black and white world for such a long time, there really is emotional life. That was a great surprise.

tV: How has it been working with the 3D element?

KF: We were really interested in both a theatrical representation of a 2D world, which we usually don't have in theatre either, and then bringing it in to 3D. We are in a traditional proscenium theatre that puts the audience at a distance looking in to the world, and we have these sliding panels that allow us to create comic books on stage where there's action and projected text. Here (indicates stage left on set model) there is a fire pole where the actors can quickly zip down and be in it again, so there's that kind of motion and fluidity within this panelled world.

Our projection comes from both the rear and the front. When it comes from the front, the actors have to be quite careful not to create shadows on the set, but when it comes from the rear you can really go right up to it and it's quite a visceral world.

We've experimented with all kinds of tropes within that 2D and 3D and use 2D props that bring us to that in-between world. The 2D wine glass that is secretly flipped to show a lower level of liquid.

It's a playful world because it is the comic books: it's entertaining.

tV: What was it like to get this kind of project off the ground?

KF: The way that our company works is it usually takes three to five years to develop a new piece. We do workshops every year and in-between the workshops I'm writing drafts of the play and communicating with designers hearing their ideas. We like to work with the same actors over long periods of time so we're hearing their ideas, character ideas, and questions. This really allows a richness to it that I don't think you get in a playwright led process where the playwright just presents a play and then stages it. It's a much more collaborate process: one where we really value theatricality, love imagery, trickery, and all kinds of things.

Before we have a play at all, we have a knowledge of what is theatrically interesting in the world, and then we can structure the play to hit all of those things.

I never start writing a play until I know what the set design is because if I know I have a fire pole, well there are ten fun things I can do with that. It is also true in Canadian theatre, that when you go into rehearsal that's the most expensive part, so we want to know a lot before we get actors and stage management in the room.

We're very lucky that we were able to raise the funding: that's a big part of our process. To be able to have five weeks to create this feels, in our economy, a luxurious amount of time to create and to be able to really refine. We're two weeks into rehearsal right now and we're getting to the point where the play is blocked and we're able to refine, and tighten, and go further, and really explore cartoon bodies, and that kind of thing.

..............................

Fanconi wrote and directs this ambitious piece and has an incredible team of artists on board: Award winning animator Paul Dutton (Triplets of Belleville), video designer Keith Murray, costume designer Christine Reimer, and lighting designer William Hales. It also boasts a line-up of prominent local talent like Amitai Marmorstein, Robert Salvador, and Dawn Petten.

You'll want to catch this show while it's here, but as Fanconi points out, “Even though Superman appeals to all ages, this particular play is for adults.” After Shuster lost his job at DC Comics, he worked for a while in fetish comics. “We have stage scenes of very graphic cartoon bondage and it's not for kids.”

Click on Nothing But Sky for tickets and show times.

KF: The way that our company works is it usually takes three to five years to develop a new piece. We do workshops every year and in-between the workshops I'm writing drafts of the play and communicating with designers hearing their ideas. We like to work with the same actors over long periods of time so we're hearing their ideas, character ideas, and questions. This really allows a richness to it that I don't think you get in a playwright led process where the playwright just presents a play and then stages it. It's a much more collaborate process: one where we really value theatricality, love imagery, trickery, and all kinds of things.

Before we have a play at all, we have a knowledge of what is theatrically interesting in the world, and then we can structure the play to hit all of those things.

I never start writing a play until I know what the set design is because if I know I have a fire pole, well there are ten fun things I can do with that. It is also true in Canadian theatre, that when you go into rehearsal that's the most expensive part, so we want to know a lot before we get actors and stage management in the room.

We're very lucky that we were able to raise the funding: that's a big part of our process. To be able to have five weeks to create this feels, in our economy, a luxurious amount of time to create and to be able to really refine. We're two weeks into rehearsal right now and we're getting to the point where the play is blocked and we're able to refine, and tighten, and go further, and really explore cartoon bodies, and that kind of thing.

..............................

Fanconi wrote and directs this ambitious piece and has an incredible team of artists on board: Award winning animator Paul Dutton (Triplets of Belleville), video designer Keith Murray, costume designer Christine Reimer, and lighting designer William Hales. It also boasts a line-up of prominent local talent like Amitai Marmorstein, Robert Salvador, and Dawn Petten.

You'll want to catch this show while it's here, but as Fanconi points out, “Even though Superman appeals to all ages, this particular play is for adults.” After Shuster lost his job at DC Comics, he worked for a while in fetish comics. “We have stage scenes of very graphic cartoon bondage and it's not for kids.”

Click on Nothing But Sky for tickets and show times.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed